March 19, 2025

Steel Wheels on a Steel Interstate?

ABOVE: A tongue-in-check meme of Brightline West’s planned used of the medium of I-15 for their Vegas-SoCal high-speed railway through the Mojave Desert

A Road to High-Speed Rail?

High Speed Trains on the NYS Thruway? That is an idea that some in the NYS Senate want to explore, as found at the bottom of page 105 in the Senate budget proposal (Senate Resolution No. 488) for 2025.

The NYS Assembly's bill would add $35 million in authorized capital funding to the Passenger Rail program and adds language to encourage or fund additional engineering staff at DOT. The Senate's bill only includes $500,000 for a study to determine whether the NYS Thruway's right-of-way could be used for the construction of a high-speed rail line.

As stated by Executive Director Steve Strauss on our organization’s Facebook page on Monday (3/18) ESPA doesn't regard the study in the senate bill as particularly useful but is not actively opposing it. Without a properly funded and staffed organization to plan and manage an intercity rail program, and notions of building “higher or high-speed rail” is just crayons on a map.

For what New York State needs, look at the sizable rail divisions at Caltrans, NCDOT, WSDOT, and separate rail-transit agency and rail authority in Virginia for comparison. I've been told that Brightline has a core group of about 80 employees overseeing the consultants and contractors for the Vegas-SoCal "Brightline West" project. The San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission overseeing Amtrak and ACE commuter rail in the Central Valley of California as about 50 employees.

In contrast the Rail Bureau in NYSDOT has about two dozen employees, primarily working on freight rail issues. Building up the institutional capacity is the first step, bringing inhouse within NYSDOT the necessary staffing and knowledge to properly advise the legislature, governor, the public on options for improving and expanding our state-supported intercity rail service operated under contract by Amtrak, doing the upper-level planning and engineering work, overseeing necessary consultants and contractors.

Planning and Management of the Empire Corridor

The great potential of the Empire Corridor has been repletely stymied by a lack of institutional capacity at the state level necessary to envision, plan, build, and manage investment in intercity passenger rail infrastructure and services. This needs to change if Upstate NY is to ever be served by a modern intercity rail service.

ABOVE: The I-90 NYS Thruway westbound approaching the Schoharie Creek bridge.

A Thruway for Fast Trains... or Not?

One the idea of using the NYS Thruway for high-speed rail, it is one with some significant problems. Yes, in Florida, Nevada, and California the private passenger rail company ‘Brightline’ is making use of highway right-of-way for hosting new high-speed tracks, but topographical conditions are very different in those locations than in Upstate NY will its landscape of rolling hills and valleys. For Brightline West, the steep Cajon Pass and “basin and range” topography of the Mojave Desert will limit speeds of the future Vegas-SoCal high-speed trains in many places.

The high-speed rail YouTuber ‘Lucid Stew’ has illustrated this in several of his videos, including his ‘Taking Back the Streets’ series of videos examining the use of highway lanes for high-speed tracks. In the ‘Cascadia Edition’ looking at the right-of-way of Interstate I-5 from Eugene, Oregon in the south through Portland and Seattle to Vancouver, B.C. in the north found many constraints on top speeds, with overall average speed being in the 80 MPH range of Amtrak’s Acela on the Northeast Corridor.

Replacing Roads with High Speed Rail | Taking Back The Streets Cascadia Edition

The I-90 NYS Thruway is clearly unsuitable as a right-of-way for High-Speed Rail east of Utica through the Mohawk Valley due to curvature, grades, and running through the middle of several small towns. Same for south of Albany as it runs along the hills west of the Hudson River. The route of the I-87 to New York City is also much longer than the current Amtrak route down the Hudson Line. East of Utica the right-of-way is more suitable for high-speed rail, but the I-90 also bypasses downtown Rochester by eight miles, with no obvious pathway to connect the Thruway to the current rail station.

ABOVE: The I-90 NYS Thruway eastbound just pass the Iroquois Travel Plaza and the big hill south of Little Falls in the Mohawk Valley

Super Express Trains

At risk of receiving some derision from fellow ESPA members (Bruce Becker, ESPA President Emeritus is shaking his head at me) I would like to show how a pragmatic plan for “high-speed rail” to Upstate NY could be built upon the ALT 90B Service Development Plan of the Empire Corridor High Speed Rail Tier I Final Environmental Impact Statement, as opposed to rejecting and replacing it after over a decade of work.

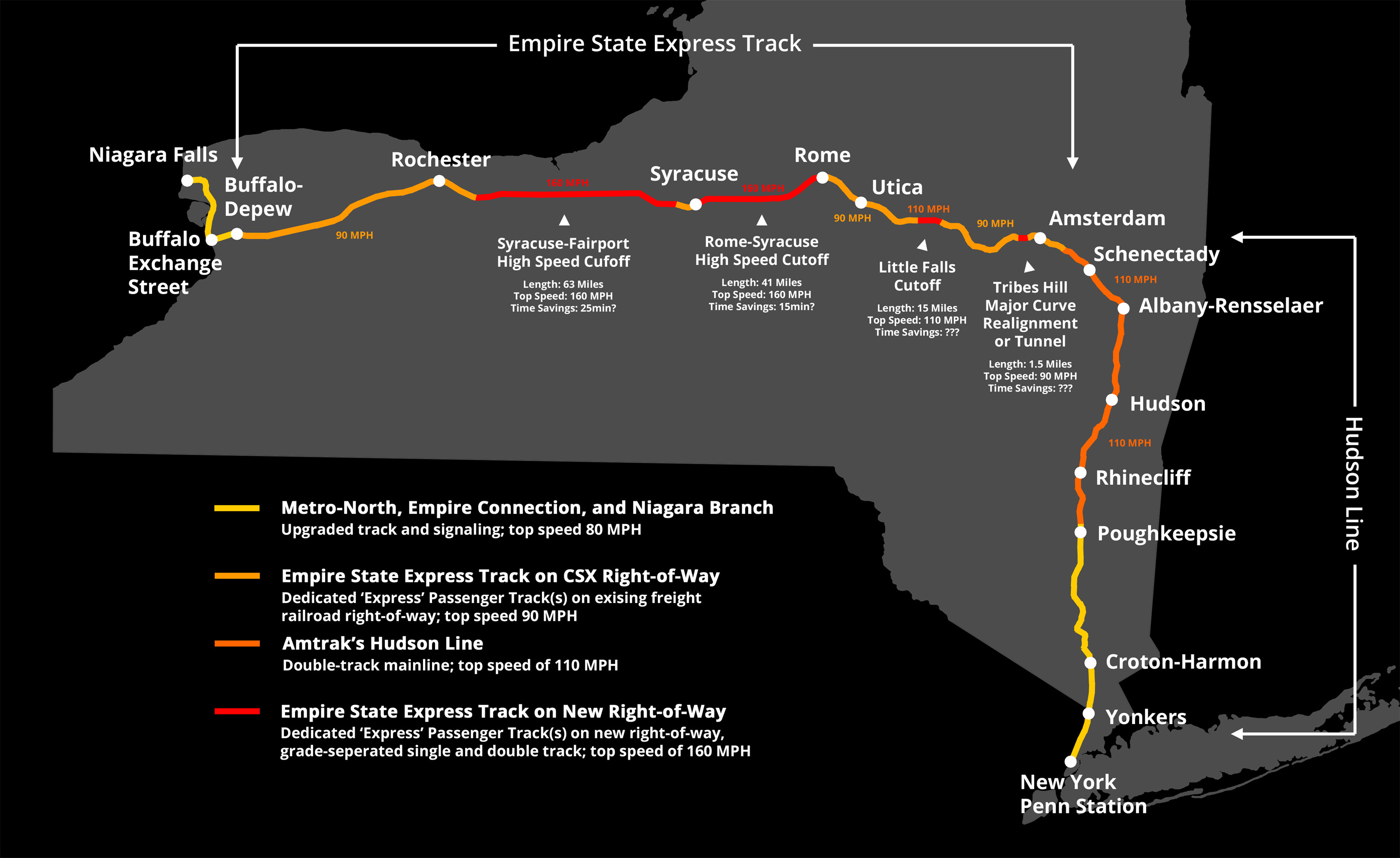

ESPA strongly supports the ALT 90B Service Development Plan, seeing it as the best way to bring a modern intercity passenger rail service – equivalent to that now offered by Brightline between Miami and Orlando in Florida – by leveraging the surplus right-of-way of the formerly four-track New York Central mainline (now owned and operated by Class I freight railroad CSX Transportation) for building a new “Dedicated Express Track” for 90 MPH passenger trains.

For ESPA, ALT 90B represents a “good enough” plan that would deliver significant improvements in long-distance mobility and environmental sustainability at a cost to construct that New York State can afford, and in a timeframe short enough to relevant to the lives and plans of people today. ALT 90B avoids the problems of the land acquisition of greenfield high-speed rail construction in California and with Texas Central, where rural property owners legally and politically fighting eminent domain, have delay construction for years while increasing costs.

Empire Corridor Tier One FEIS: ALT 90B Service Development Plan

The 2014 Draft EIS examined and rejected two alternatives for 160 and 220 MPH high-speed rail for their high estimated cost of $27 and $39 billion, costs which are likely an underestimate given that the cost estimate to complete Phase 1 of the California HSR project have gone from $33 billion in 2008 to $106 billion in 2024, with the completion date slipping decades into the future. Building an entirely new greenfield high-speed railway between New York City and Buffalo would in all likelihood cost many tens of billions and take several decades to complete.

Still, with this stated, the Service Development Plan could be altered in a way to incorporate segments of “true high-speed rail” to further reduce travel times from those in ALT 90B, and most importantly not delay more immediate investment in the Empire Corridor as laid out in the Service Development Plan. There is $2.5 billion in proposed work (some of it, like the $634.8 million Livingston Ave Bridge replacement has $215 million in federal funding) that over ten years would fully rebuild the Hudson Line and allow for an additional Amtrak frequency west of Schenectady to Niagara Falls by building segments of dedicated third track in the Mohawk Valley.

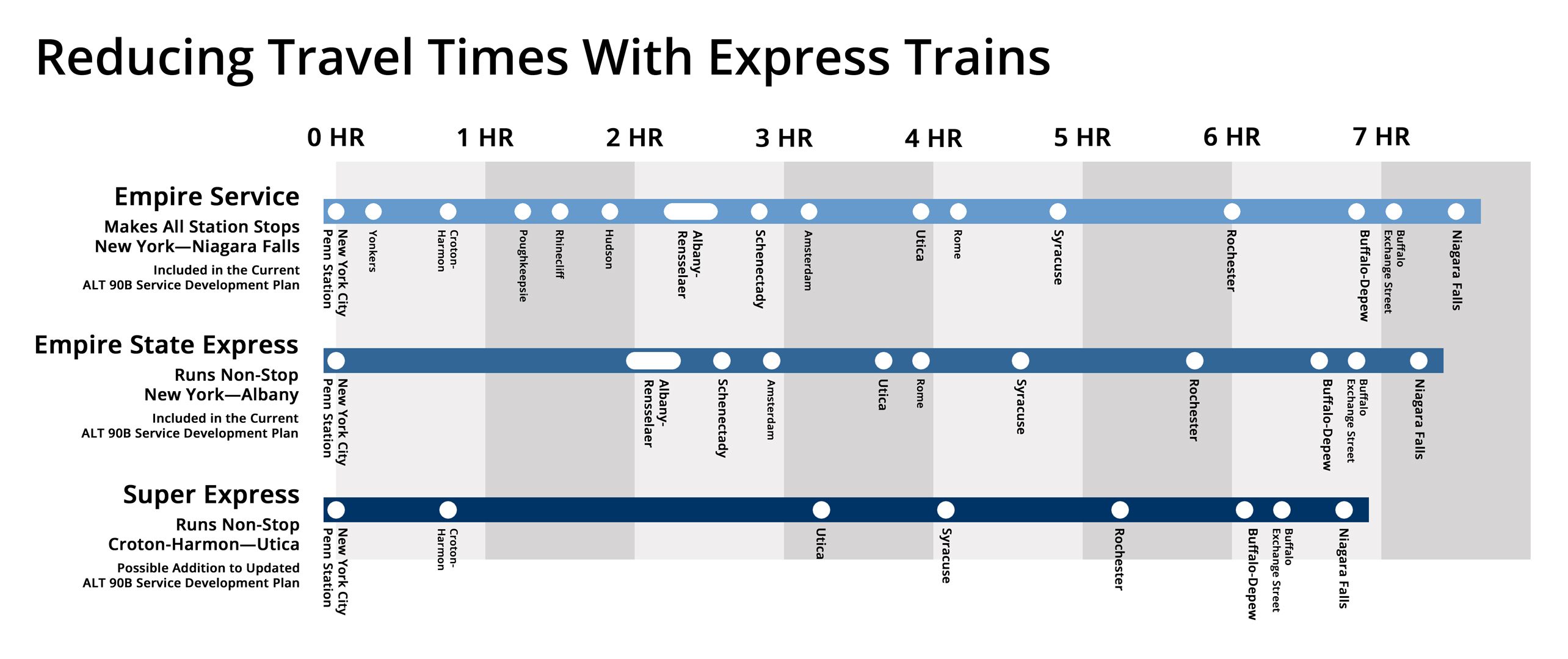

So where to start? Well, the key to reducing travel times is not just going faster but not slowing down or stopping. Without any very high-speed rail track travel times to Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls could be cut by a full 45 minutes by running a few daily non-stop express trains – morning, midday, and evening perhaps – between Croton-Harmon and Utica.

From the Service Development Plan, we know that for the proposed “Two Cities—Two Hours” non-stop NYC-Albany express that 5 minutes are saved for each station between Croton and Rensselaer, 15 minutes total for Poughkeepsie, Rhinecliff, and Hudson. No time is saved by not stopping at Croton-Harmon as Amtrak trains are slotted into the regular busy traffic of Metro-North commuter trains, the 32 miles from Penn Station to Croton-Harmon being the slowest segment of the entire Empire Corridor, taking 40-to-45 minutes, an average speed in the low forties. Not stopping at Schenectady, Amsterdam, and Rome would save another 15 minutes, and running non-stop through Rensselaer saves the 15 minutes of the usual layover.

With the ALT 90B travel times as the base, that brings travel times to and from New York City to 3h 10m from 3h 55m for Utica, 4h 05m from 4h 50m for Syracuse, 5h 15m from 6h for Rochester, 6h 05m from 6h 50 for Buffalo-Depew. Average speed between Croton-Harmon (let’s assume it remains as a suburban stop) and Utica would be 84.8 MPH, all without going above 110 MPH on the Hudson Line and then 90 MPH on the new “express track” of ALT 90B along the CSX mainline through the Mohawk Valley.

Not-stopping is the key, in the early 1960s the SNCF (French National Railways) ran several express trains with averages over 80 MPH despite not having a top speed on the national system above 93 MPH (150 KM/H) – the Le Mistral from Paris to Dijon covered the 195.3 miles in 146 minutes, for an average of 80.3 MPH. Once the express cleared the urban center the driver was able to bring the train up to 93 MPH on the superbly built and maintained mainline and keep it there till the next station.

The SNCF developed an operating pattern of grouping intercity trains into morning, midday, and evening ‘flights’ so to limit interference with freight trains, with a fast limited-stop first-class express departing, followed by a slower all-stops first and second-class intercity train serving smaller intermediate cities not served by the first class express. This is the same service pattern seen today on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor with the Acela and Northeast Regional. The same could be done on the Empire Corridor, for example a 7 AM express departing Penn Station, followed at 7:15 AM standard train that while 15 minutes behind the express would by Syracuse a full hour behind. This pattern would provide Utica, Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, and Niagara Falls with the fastest travel time possible, while ensuring that smaller cities like Hudson and Amsterdam would be served as well with multiple daily trains. The Service Development Plan calls for eight daily roundtrips NYC-Buffalo, increase this to eleven and then three can be super-express trains connecting New York City with Central NY and Western NY.

This would bring to the 461-mile-long Empire Corridor an intercity rail service comparable in average speeds between stations to the 457-mile Northeast Corridor, and the much shorter 235 mile ‘Brightline’ service between Miami and Orlando. I think that this would be a very good addition to the Service Development Plan has it would only require additional and/or longer segments of third and fourth dedicated passenger tracks so that opposing passenger trains can pass at speed.

What is essentially proposed in ALT 90B is a new “Alternating Double-Single Track” line for passenger trains from the Capital District to Buffalo-Niagara, paralleling and interacting very little with the existing double-track mainline, like a HOV lane fully segregated from the rest of the freeway lanes. This is high-speed rail design strategy coined by Spanish academics for cheaper construction of lower trafficked high-speed lines, and is being utilized by Brightline for both their Florida and Vegas-SoCal ‘Brightline West’ services.

ABOVE: A Siemens diesel trainset racing over Brightline’s new 125 MPH track along the SR 528 Beachline Expressway in Florida between Cocoa and Orlando Int. Airport. The rail corridor is fenced and there are no public grade crossings. IMAGE CREDIT: Roaming Railfan through Brightline Press Kit

High Speed Cutoffs

So, this brings us to incorporating “true” very high-speed rail infrastructure to the ALT 90B Service Development Plan, because, hey, we want “real” high-speed rail! Well, let me introduce the concept of railroad cutoffs, a new rail line built to replace or supplement an existing route, typically one where the old line is deficient for some reason – including a longer route, sinuous track, heavier grades, and/or over-capacity. Many were built at the turn of the 20th Century in America and include the famous Nicholson and Lackawanna cutoffs of the Lackawanna Railroad (DL&W) through New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York State, which provided their Hoboken-Buffalo mainline with a more direct route with gentler grades and straighter track.

The same could be done for the Empire Corridor, to reduce travel times even further, diverting the new “express track” from the CSX right-of-way to free it from some of the constraints, including the 90 MPH limit imposed by CSX. But were to do this? Well while the Mohawk Valley might be an obvious place, but in fact 90 MPH can be maintained for most of the route from Hoffmans east of Amsterdam where the Hudson Line merges with the CSX mainline, and the average speed Amsterdam-Utica under ALT 90B is 80 MPH. Two places where speed falls below 90 MPH is the current 50 MPH curve at Tribes Hills a few miles east of Amsterdam which would be improved to 70 MPH in the Service Development Plan, the Draft EIS proposing a deeper cut into the hillside (or a tunnel) for a 90 MPH curve. There is another 50 MPH curve at 645 foot promontory of ‘Big Nose’ east of Canajoharie, which under ALT 90B would be eased to 90 MPH by running the express track under a new viaduct carrying Route 5 around the cliff face.

The sharpest curve is at Little Falls where even under ALT 90B it would be a 60 MPH curve, here is where a 15-mile cutoff might be built. The new express track could diverge from the CSX mainline after St. Johnsville and start rising up parallel to the CSX right-of-way till crossing the freight line and the Mohawk River, plunging into a two-mile tunnel before crossing the river and then the freight line again before fully joining with the CSX right-of-way after crossing West Canada Creek and entering Herkimer. How much time would be saved by avoiding slowing for a 60 MPH curve while running up to 110 MPH for about ten miles? I’m not qualified to estimate, but likely two or three minutes perhaps.

The next place for a cutoff I think is Rome to Syracuse, due to the opportunity of having the new express track diverge right after the Rome Station to a new right-of-way off yet parallel and adjacent to the CSX mainline running to Verona where the track (or tracks) could like Brightline run along the shoulders of the NYS Thruway to the interchange with the I-481 where it would have rise up on a viaduct through the suburbs of Syracuse till curving south for about 3000 feet to follow the CSX mainline on the northside a further 2000 feet to the existing Syracuse Station.

A big advantage of this cutoff would avoid the freight traffic of the CSX Dewitt Yard in East Syracuse. To make room for a high-level island platform the watercourse Beartrap Creek would need to be shifted a bit north, or the tracks and platforms built on a viaduct. An overhead pedestrian bridge could connect across the freight tracks to a new station house and parking garage. How much time would save? Well, if you figure a 100 MPH average speed, then about 15 minutes over ALT 90B, bringing Syracuse within 3h 50m of New York City for express train, and 3h 35m for an all-stops train.

The next and last cutoff could be from Syracuse to Fairport – the existing CSX mainline having a number of curves between Savannah and Palmyra that in ALT 90B would reduce speeds several times to 80 and 70 MPH even after realignment – with the express track diverging from the CSX right-of-way after the NYS State Fair to utilized an abandon interurban rail bed parallel and between the NYS Thruway and CSX mainline till crossing the I-90 in Jordon south of Cross Lake, heading northwest across the Seneca River/NYS Barge Canal to a major east-west power transmission corridor to just east of Fairport where the express track would parallel and then rejoin the CSX mainline into Rochester.

ABOVE: Locations of possible high-speed cutoffs that be integrated into an improved ALT 90B Service Development Plan could reduce travel times further to Central and Western NY from New York City.

Following a power line is the strategy of the Texas Central Railway high-speed rail project between Houston and Dallas, engendering a lot of legal and political opposition from rural landowners. The post-glacial terrain of north-south low drumlins and shallow tunnel valleys would require the cutoff to alternate between earthen fills, viaducts, and deep-cuts as the ridgelines of drumlins are intersected one after another. This is the route of the proposed high-speed rail tracks of the rejected ALT 125 of the Draft EIS.

How much time would be saved? Well, once again if you figure a 100 MPH average speed for the 76 miles (three miles shorter than the CSX mainline) then about 24 minutes, which rounded up to 25 minutes would require a 101 MPH average speed. That, combined with the 15 minutes from the Rome-Syracuse Cutoff would reduce New York City to Rochester travel time to 4h 35m for a express train and 5h 20m for an all stops train; travel times to Buffalo-Depew to 5h 25m for express trains and 6h 10m for all stops trains; and travel times to Niagara Falls to 6h 11m for express trains and 6h 56m for all-stops trains.

This, all combined together would allow passengers to travel between New York City and Niagara Falls on both express and all-stops trains faster than Boston to Washington DC on Amtrak today, either by the Acela or Regionals. It wouldn’t be Chinese high-speed rail, but it would be very much like what exists in Europe where new high-speed lines have been incrementally built over several decades as integrated upgrades to the existing rail systems. Ride a German ICE (InterCity Express) train of Deutsche Bahn and you will travel over both upgraded mainlines and new high-speed lines as you journey across Germany.

ABOVE: The fastest passenger service outside the Northeast Corridor is offered by Brightline between Miami, West Palm Beach, and Orlando. The service utilizes primarily the upgraded mainline of the Florida East Coast Railway with speeds of 80-to-110 MPH, but there is a 32-mile segment of 125 MPH track on new right-of-way from Cocoa to Orlando Int. Airport. IMAGE CREDIT: Roaming Railfan through Brightline Press Kit

What Kind of High Speed Train?

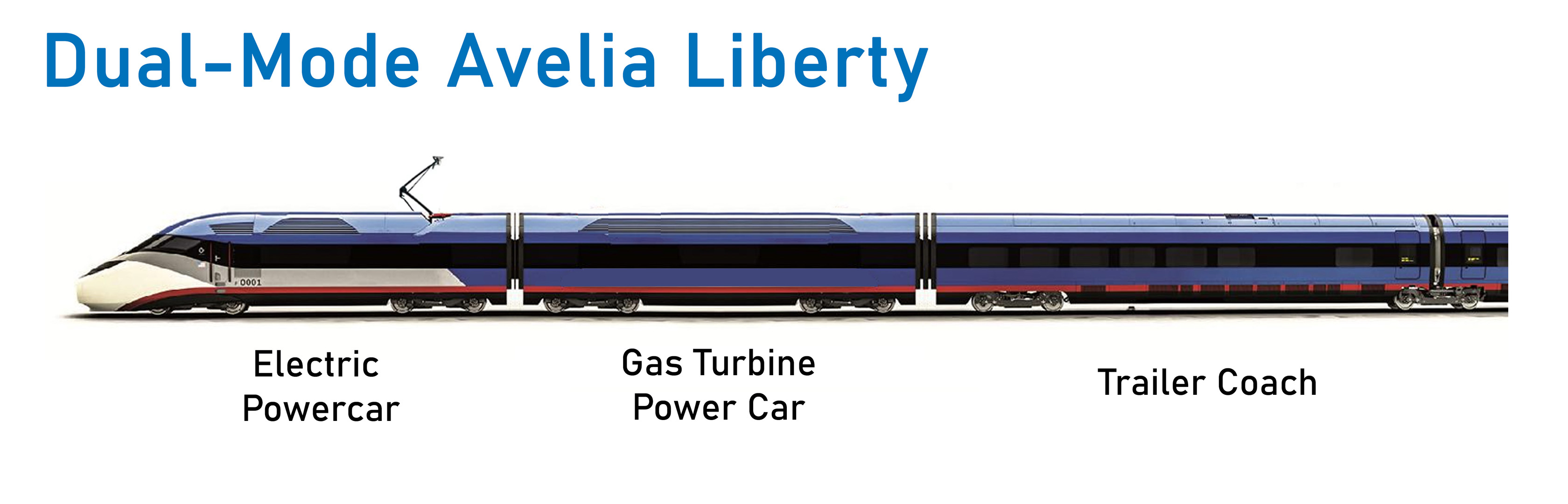

One last issue that needs to be addressed, is electrification. In Europe and Asia where railways are state-owned, this is merely a matter of cost, and with most major mainlines already electrified, new high-speed lines can just seamlessly dovetail into the existing network. In America however, the situation is very different and little of the network is electrified and most of it is privately owned, and the freight railroads that own the tracks are very much opposed to electrification, and CSX will like 110 MPH speeds, not allow it on its right-of-way. That means that while Hudson Line (Amtrak and MetroNorth) could be electrified, the new express tracks on CSX right-of-way cannot.

The new Siemens Charger-Venture ‘Airo’ diesel trainsets that Amtrak will be introducing on the Empire Corridor at the end of this decade have a top commercial speed of 125 MPH, and are of the same model as the trains utilized by Brightline in Florida where there is 30 miles of 125 MPH running on the new track between the Orlando International Airport and Cocoa on the Atlantic Coast. Like Brightline, future trains could run up to 125 MPH on the two proposed cutoffs and likely average at least 100 MPH. Utilizing renewable diesel would also significantly cut carbon emmissions.

However, to go faster and reduce emissions by utilizing electric propulsion, there is another possible solution that would allow speeds of up to 160 MPH on the two cutoffs. In Spain to allow high-speed services to travel over some unelectrified lines to provincial destinations, the solution has been to add two diesel generator cars adjacent to the two end electric power cars (locomotives) to power the “Talgo 250 Dual” trainsets when running beyond the wires. The same could be done in America to greater effect, where so little is electrified.

Over two decades ago the Federal Railroad Administration and manufacture Bombardier designed, built, tested, and promoted the ‘Jet Train’, a gas-turbine version of Amtrak’s all-electric Acela Express trainset. The compactness and lightweight of the high-power gas-turbine allowed the locomotive to travel up 150 MPH while producing lower dynamic track forces than a conventional Amtrak train at 90 MPH, keeping track maintenance costs down. Also due to its lighter weight and modern engine, the JetTrain had greenhouse gas emissions 30% lower than a then diesel unit operating at the same speeds.

Sadly, Bombardier found no buyers, but today Alstom (which bought Bombardier in 2020) could dust off the plans of the JetTrain and examine the forgotten locomotive still stored at FRA’s Transportation Technology Center in Pueblo, Colorado, to create a gas-turbine generator car that could be inserted into a Avelia Liberty trainset (replacing old Acela trainsets) like the Talgo 250 Dual, that would then feed electricity to the traction motors of the two electric power cars for running over unelectrified tracks up to 110 MPH. That would allow the two proposed high-speed cutoffs to be electrified with speeds increased to 160 MPH, with the gas-turbine car powering the high-speed train when on CSX right-of-way. Alternatively, you could like the JetTrain just power an Avelia Liberty on gas-turbines alone, using renewable diesel as fuel, and potentially later hydrogen to get to net-zero carbon emissions.

Conclusion

So, there you have, a pragmatic plan to bring “high-speed rail” to Upstate NY that would be build out of the existing ALT 90B Service Development Plan and wouldn’t delay most of the proposed ALT 90B projects within the first ten years of the proposed 25-year program. It requires some out-of-the-box thinking and some comprises as compare to high-speed rail in China, its clearly not a perfect but a good enough plan, which is why ESPA strongly supports ALT 90B of the Final EIS as it is, with a 90 MPH express track build along the existing CSX right-of-way, Schenectady to Buffalo. The current ALT 90B plan has an estimated cost of $8 billion, with my proposed cutoffs its a fair guess that costs would raise closer to $12 billion, if not higher.

Still, if lawmakers want to explore further reductions in travel times and increases in speed beyond the current ALT 90B Service Development Plan, these are the explorations that I would suggest be analyzed by professional railway engineering consultants, which build upon and dovetail with the great amount of work which as been accomplished to date. Foremost the focus the attention of lawmakers needs to be on building up the organizational capacity to plan and execute a intercity passenger rail mega-project, while finding potential major funding for it as well.

Benjamin Turon

ESPA Vice-President

Opinions expressed in this piece are the author’s own.